滋賀県立大学 永井拓生+サステナブル構造デザイン研究室

THE UNIVERSITY OF SHIGA PREFECTURE

滋賀県立大学 永井拓生+サステナブル構造デザイン研究室

THE UNIVERSITY OF SHIGA PREFECTURE

滋賀県立大学 永井拓生+サステナブル構造デザイン研究室

THE UNIVERSITY OF SHIGA PREFECTURE

Sustainable Structural Design Using Shiga-Grown Reed

Writer: Takuo Nagai

For roughly the past decade, we have researched the use of reed in architecture. Because there are many specialized books—and plenty of online resources—explaining “what reed is,” we will focus here instead on how we came to encounter reed as a material.

Encountering Reed

It all began in 2015, when I was invited by architect Prof. Takeo Matsuoka (now Professor Emeritus) of the University of Shiga Prefecture to join a community planning workshop in Omihachiman City. About thirty students and local residents gathered in a local meeting room to discuss regional challenges and envision the town’s future together. At the end of the workshop, several groups presented their ideas. Hearing local participants repeatedly emphasize the importance of “utilizing reed” and “conserving the reed beds,” I realized how deeply reed is woven into the life and identity of this region.

On the way back to Hikone City, where our university is located, I stopped near Lake Nishi-no-ko, the largest of Lake Biwa’s peripheral lagoons, and picked up a stalk of reed. Until then, I had admired the reed beds from a distance through the car window and thought they were beautiful. However, it was my first time seeing and touching them up close. Standing beside the reed bed, I was struck first by the height—from ground to tip, it reached about 4–5 meters. Even more surprising was that, at the base where it is thickest, the diameter was only about 1 centimeter. I could hardly believe it.

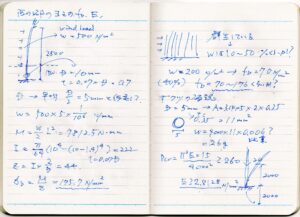

I did a quick calculation on the spot to estimate how “strong” reed might be. Figure 1 shows the notes I jotted down at the time. As a structural engineer, I routinely calculate what kinds of forces act on a building’s columns and beams—and how large those forces are. Wherever I am, as long as I have paper, a pen, and a calculator, I can run structural calculations with accuracy sufficient for design purposes.

Figure 1. Notes from a quick calculation of reed strength and stiffness in the reed bed

In my notes, I wrote that the bending strength of a reed culm, σb, would be 70–176 N/mm², and the Young’s modulus, E, would be 28,128 N/mm². Later, I looked up the material properties in more detail; the numbers were within a plausible engineering range. The calculation took only three to four minutes. When I saw the values on my calculator, I couldn’t help but grin to myself. They were higher than those of wood commonly used in building structures—and at the time, I was probably the only one who noticed. (I soon found out, though, that this was not the case as I continued my research on reed…)

“This could lead to something truly interesting—something that would surprise people.”

Designing a Pavilion with Reed as the Structure

After that, we conducted some simple strength tests at the university, which further confirmed that reed has remarkably good mechanical performance. Even so, for students and local residents who are not specialists, it is hard to grasp whether those numbers are actually high or low. I created several concept images of pavilions and spatial designs using reed and showed them to students and presented them to local community members. At first, however, the ideas seemed to be viewed as eccentric and unrealistic.

Yet as people began to work with their hands—touching the reed, assembling frames, and building mock-ups (Figure 2)—they gradually realized that it was not merely a fantasy. The intriguing spaces they had imagined started to feel real. If it were just an unbuildable design studio exercise, one could cut corners. But once we knew it could actually be built, we could not. Local residents were eagerly anticipating the outcome as well, and there was no turning back. Before long, every summer vacation was consumed—morning and night—by design work and preparation for fabrication.

In this way, from 2016 to 2018, we built one reed pavilion each year.

Figure 2. A lightweight yet strong reed structure

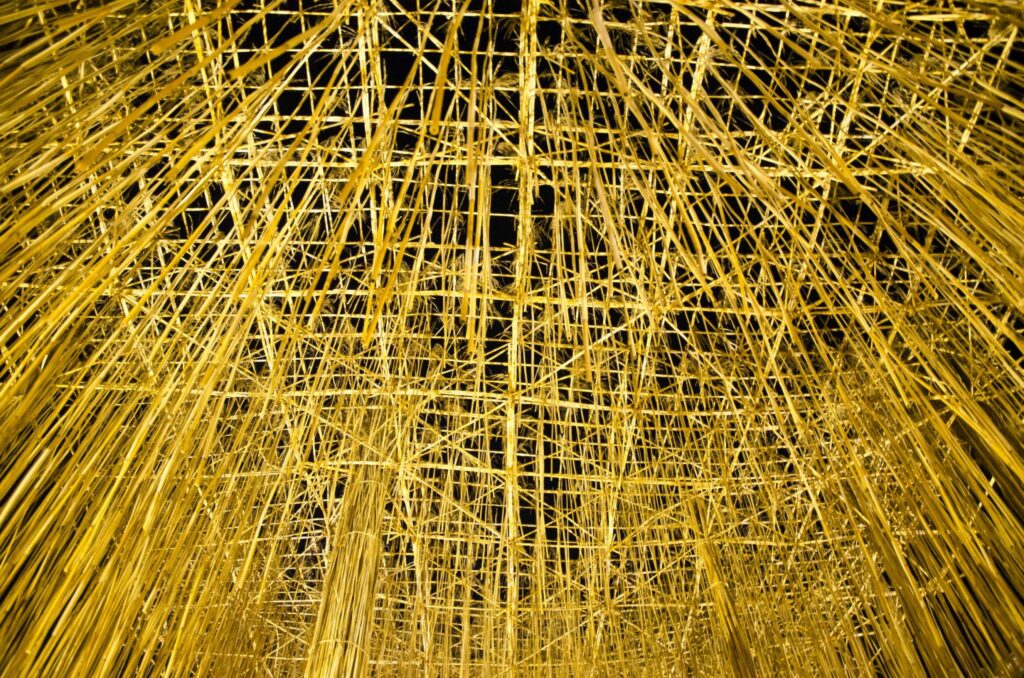

Figure 3 shows the first project, the “Reed Dome.” It is a dome-shaped space built on a long, narrow site along Hachiman-bori Canal. Thousands of reed stalks were connected using thin tying wire and cable ties, forming a robust structural body. After the exhibition period at Hachiman-bori ended, the pavilion was relocated to La Collina Omihachiman, where many visitors enjoyed the space.

Figure 3. Reed Dome

Figure 4 shows the second project, the “Reed Pavilion.” We used bundles of reeds—commonly seen after reed harvesting—as columns, placed a reed-structure roof above them, and suspended thousands of reed stalks from the roof. The result was a space that allowed visitors to feel as if they had stepped into a reed bed, even while remaining in the town.

Figure 4. Reed Pavilion

Figure 5 shows the third project, the “Reed Cocoon.” It was built in the rear garden of a traditional machiya townhouse in Omihachiman’s former castle town district. With the theme of combining geometric forms made from reed with traditional techniques, we created a small dome in the shape of a true sphere. Inside the dome, a suikinkutsu (water harp) was installed beneath the ground, allowing visitors to enjoy a quiet, contemplative space filled only with the sound of dripping water.

Figure 5. Reed Cocoon

A New Challenge in Utilizing Reed: Developing Reed-Based Strand Board

In recent years, we have been working to establish ways to use reed on a much larger scale. To begin with, how much reed can actually be harvested from the reed beds spreading around Lake Nishi-no-ko? The reed-bed area around Lake Nishi-no-ko is approximately 120 ha. Stand density ranges from 30 to 100 stems/m², which corresponds to roughly 500 to 1,500 g/m² in biomass. Although this varies with management conditions and other factors, on average it means that about 600 to 1,800 tons of reed grows across the entire Lake Nishi-no-ko area each year. By contrast, the amount of reed used in each of the pavilions mentioned earlier was only a few hundred kilograms at most.

There is great value in proposing intriguing structures and beautiful spaces using reed harvested from only a small portion of the reed beds. However, to properly manage extensive reed beds, it is also important to create a stronger need to harvest and utilize reed in much larger quantities. This is why we are tackling the development of reed-based strand board (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Prototype of reed-based strand board

A strand board is a panel product made by slicing wood or other raw materials into thin strands, blending them with adhesive, and then hot-pressing the mat into a board. It is used for a wide range of applications, including furniture and interior finishes. OSB (oriented strand board)—often seen at home improvement stores—is one type of strand board.

Because reed has properties that can surpass those of wood, we believed it should be possible to produce a high-performance strand board from reed, and we began making prototypes. However, it turned out not to be so straightforward. Reed does not bond well with adhesives, so even though the material itself performs well, its performance is not fully realized once it is made into a board. Even so, we have found that repeated improvements and careful refinements can enhance its properties. Reed-based strand board is still under development.

Another challenge is that, because the reed is broken down into small pieces, it becomes difficult to sense the material’s “reed-like” character in the finished board. From chip-like particles, one can hardly imagine the reeds swaying in the wind along the lakeshore. This led us to develop what we call “Reed Mesh”—a method for making a panel while retaining a sense of reed.

Reed Mesh is a molded board in which thin strands, split along the fibers of the culm, are arranged in a sparse, open lattice. It expresses the image of countless reeds overlapping in a reed bed. “Naiko,” peripheral lagoons in Japanese, in Figure 7 is an interior design that uses Reed Mesh. In the large space of a former sake brewery in the old castle town district, gently curved mesh panels are suspended from the ceiling. The shimmering effect created by transmitted and reflected light produces an experience akin to being beneath the surface of the water.

Figure 7. Naiko — A Nostalgic Landscape of Shiga

Reed as a “Fifth Material”

The structural systems of most buildings around us have, in essence, been shaped by four materials—concrete, steel, brick, and wood. Among them, concrete and steel are indispensable because of their high strength, yet they also impose a heavy environmental burden on the construction industry, and reducing their use has become an urgent task. For this reason, timber construction is attracting growing attention worldwide.

That said, not everything can be replaced with wood. Even in regions like Shiga Prefecture, where forest resources are abundant, there are many places where procuring timber is not straightforward due to steep terrain and challenges such as maintaining forest roads. Looking internationally, Global South regions are expected to see enormous demand for buildings through the middle of this century, yet they are not necessarily rich in timber resources.

This is why research and development on a “fifth material” is now being advanced in the field of structural engineering in many countries. The idea is to find materials that can potentially substitute for concrete and steel in terms of performance, while keeping environmental impacts low—like wood.

The leading candidates are, unsurprisingly, plant-based materials. Because plants absorb CO₂ through photosynthesis as they grow, it is possible to reduce the CO₂ emissions associated with material production. In particular, high-strength plant fibers have attracted attention. For example, some experimental data suggest that flax fibers can have more than twice the strength of steel. While bamboo and reed fibers are not at that level, they still show high performance.

Research on utilizing plant-based materials as structural systems and building products will likely continue to develop in the coming years. I dream that new building materials derived from Shiga’s reed will someday spread around the world. I believe it will be the younger generation—students like those working with us today—who will make that future a reality.

Acknowledgements

None of the projects introduced in this article would have been possible without the understanding and support of local residents, and the tremendous efforts of all collaborators and students. We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to everyone involved.